Human teeth are the morphologically complex food processors of the skeleton. Through the motion of the mandible, the lower teeth are brought into occlusion (tooth-on-tooth contact) with the upper teeth in order to break down food. Teeth resist the stress and wear induced by occlusion by means of their coating of enamel, the hardest substance in the body. Like all mammals, humans have two sets of teeth, a deciduous set which functions during early life and a permanent set which gradually replaces the deciduous set.

Tooth Classes

Most adults have 32 teeth, although many people have fewer due to the surgical removal of teeth or the failure of some teeth to form. These 32 teeth are divided into four distinct classes which are differentiated based upon form and function. Both the mandible and maxilla have two symmetrical quadrants, each containing the same number of each tooth class. From front to back each quadrant bears two incisors, one canine, two premolars, and three molars.

Most adults have 32 teeth, although many people have fewer due to the surgical removal of teeth or the failure of some teeth to form. These 32 teeth are divided into four distinct classes which are differentiated based upon form and function. Both the mandible and maxilla have two symmetrical quadrants, each containing the same number of each tooth class. From front to back each quadrant bears two incisors, one canine, two premolars, and three molars.

Incisors are the blade-shaped teeth at the front of the mouth which are used primarily in slicing food during acquisition. Just behind the incisors are the canines, which in many other mammals (like dogs, cats, apes, and monkeys) are long pointed teeth used as weapons and for social displays. Human canines are much reduced in size and more closely resemble incisors than the sharp canines of many other mammals. Behind the canines are the premolars (also known as bicuspids). Premolars function by crushing foods in a similar way as the final tooth class, the molars. Molars have broad, flat grinding surfaces for breaking food into small particles.

Generalized Tooth Morphology

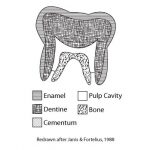

Each tooth consists of an enamel covered crown which is exposed during life and a root which anchors the tooth into the bone of the maxilla or the mandible. The junction of the root and crown is known as the cervix. The core of the tooth is formed by dentine, a mineralized tissue that is softer than enamel. The dentine surrounds the pulp cavity, which contains the nerves and blood supply for each tooth. These nerves and blood vessels are transmitted from the bone of the maxilla and mandible by means of the root canal.

Each tooth consists of an enamel covered crown which is exposed during life and a root which anchors the tooth into the bone of the maxilla or the mandible. The junction of the root and crown is known as the cervix. The core of the tooth is formed by dentine, a mineralized tissue that is softer than enamel. The dentine surrounds the pulp cavity, which contains the nerves and blood supply for each tooth. These nerves and blood vessels are transmitted from the bone of the maxilla and mandible by means of the root canal.

Molars and premolars bear two or more bumps of enamel called cusps on their occlusal surface. The organization of these cusps and their relative degree of wear allows identification of the tooth class and side. Each cusp on the molars and premolars has a name which follows certain conventions. Cusps on maxillary teeth have names which end with the suffix –cone, while mandibular cusps end in the suffix -conid.

Dental Terminology

A specialized set of directional terminology is applicable to the teeth. The mesial direction is towards the front of the mouth at midline, where the incisors from the left and right quadrants meet. Distal refers to the opposite direction. The side of the teeth which contacts the tongue is called the lingual side, while the opposite side is termed the buccal side (for molars and premolars) or the labial side (for incisors and canines). The side of a tooth which contacts another tooth during chewing is the occlusal surface.

A specialized set of directional terminology is applicable to the teeth. The mesial direction is towards the front of the mouth at midline, where the incisors from the left and right quadrants meet. Distal refers to the opposite direction. The side of the teeth which contacts the tongue is called the lingual side, while the opposite side is termed the buccal side (for molars and premolars) or the labial side (for incisors and canines). The side of a tooth which contacts another tooth during chewing is the occlusal surface.

Individual teeth are referred to by an abbreviated system involving one or two letters and a number. When the side of the teeth needs to be indicated, the letters R and L are used to designate right and left. The tooth category is indicated by the letter I, C, P, or M for incisor, canine, premolar, and molar. For all tooth classes except premolars, teeth are numbered starting with the numeral 1 for the most mesial tooth of each class. This numeral is often written as a subscript for mandibular teeth and as a superscript for maxillary dentition. Thus RM1 refers to the most mesial maxillary molar in the right quadrant while RM1 refers to the most mesial mandibular molar in the left quadrant. The system is the same for premolars, except the numbering system begins with P3. This peculiarity stems from the fact that the most mesial human premolar is evolutionarily equivalent to the third premolar of those other mammals which possess more than two premolars. Deciduous teeth are referenced using the same system, but are preceded by the letter D (e.g. DI2 refers to the second deciduous mandibular incisor).

Deciduous Dentition

The deciduous dentition, also known as the primary dentition, consists of 20 teeth which appear early in life. They are subsequently shed and replaced by the permanent dentition described above. Just as in the permanent dentition, there are two deciduous incisors and a single deciduous canine in each quadrant of the mouth. There are two deciduous teeth distal to the deciduous canine. Many human osteologists call these teeth deciduous molars because they serve the normal molar functions of crushing and grinding. However, it is more accurate from an evolutionary and ontogenetic standpoint to view these teeth as premolars. Under this viewpoint, which is adopted here, there are no deciduous precursors to permanent molar teeth. Most of the deciduous teeth resemble their permanent counterparts in morphology. As a rule, deciduous teeth are smaller, more bulbous and have thinner enamel than their permanent counterparts. Their enamel covering has a translucent, milky appearance, which is distinctive compared with the appearance of permanent enamel. Furthermore, their roots are commonly partially resorbed or eroded away starting from the root apex. The distal root tilt which is so useful for siding permanent teeth is not a reliable indicator of side for deciduous teeth.

Applications: Dental Age Estimation:

Both deciduous and permanent teeth are formed in cavities (or crypts) within the bone of the maxilla and mandible. Tooth formation begins with the crown enamel surface and continues towards the root. As they develop, teeth migrate through the bone of the jaws until they break through the surface. This event is known as tooth eruption. Deciduous teeth follow a strict mesial-distal tooth eruption sequence. Thus, deciduous incisors are the first teeth to erupt, followed by deciduous canines and premolars. The eruption sequence for permanent teeth is slightly more complex. The first molar is the first permanent tooth to appear in the mouth. Following the appearance of the first molar, the deciduous teeth are replaced by their permanent counterparts in sequence from mesial to distal. It is not until all the anterior permanent teeth are in place that the second and third molars make their appearance.

Tooth eruption sequences have been shown to be closely tied with the chronological age of individuals. In other words, not only is it true that deciduous central incisors are the first teeth to erupt, but this event occurs at approximately 9 months of age, with an average variation of +/- 3 months (Ubelaker, 1978). Variation in the timing of tooth eruption is lowest at younger ages and increases with time. Thus, dental age estimation gets less precise as individuals get older. Stages of crown formation within the bony crypts are also reliable age indicators, but observations of unerupted teeth require either physical destruction of the specimen to gain access to the tooth in its crypt or the use of medical imaging techniques such as CT scanning or traditional radiography.

Because teeth follow a strict eruption sequence, teeth are subjected to wear at different times during the life-span of an individual. This differential wear can provide additional clues for age estimation. For example, while third molar eruption times are highly variable, an individual with a heavily worn third molar is likely to be substantially older than an individual with an unworn third molar. This is simply due to the fact that older individuals have had more time to expose their teeth to substantial wear and tear. However, tooth wear rates also depend on non-age related factors, such as the amount of grit inherent in the diet. Thus, wear patterns are less precise clues to age determination and are likely to vary considerably between different human populations.